In Praise of the Diagonal Reference Line

Annotations are what set visual communication and journalism apart from just visualization. They often consist of text, but some of the most useful annotations are graphical elements, and many of them are very simple. One type I have a particular fondness for is the diagonal reference line, which has been used to provide powerful context in past news pieces, and is making a comeback in the COVID-19 charts.

One of my favorite charts ever is a piece called Why Is Her Paycheck Smaller? by Hannah Fairfield and Graham Roberts. It's a beautiful piece, but since it's from 2010 it's no longer working as an interactive chart (because Flash). The key elements can be seen on a simple screenshot, though.

The chart shows men's weekly earnings plotted on the horizontal axis against women's earnings on the vertical. That's just a simple scatterplot, but what makes this so effective is the heavy diagonal line showing equal wages. Notice where most of the dots are? But what makes this really special are the additional lighter reference lines showing 10%, 20%, and 30% less for women's earnings compared to men doing the same job. Without those, it would be incredibly hard to appreciate that difference or to understand it with anywhere near that precision.

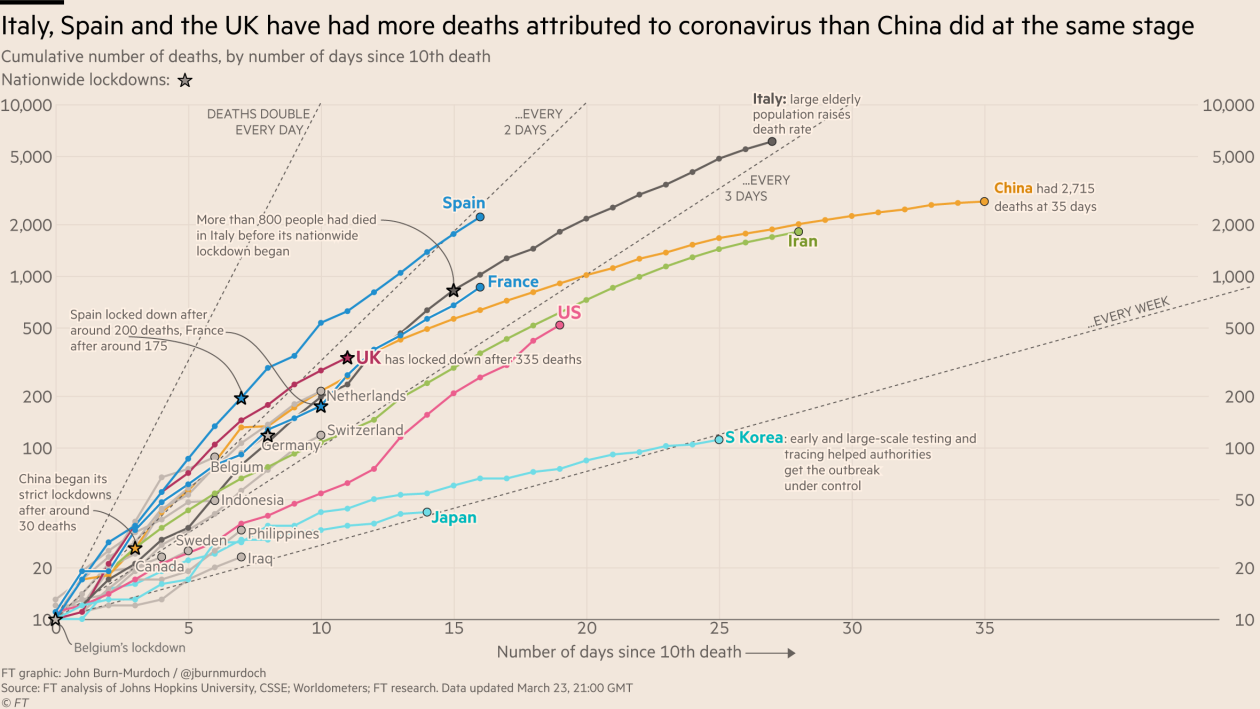

John Burn-Murdoch has been doing incredible work tracking COVID-19 cases over the last few weeks. His coronavirus pandemic charts at the Financial Times give a very clear perspective of how different countries compare. This particular chart shows the number of deaths from the coronavirus on a vertical log-axis, with the horizontal axis being indexed to start at whenever each country first crossed 10 deaths.

Notice the reference lines? They're showing different rates of growth, here expressed as the days each country takes to double its deaths at the current rate: every day, every other day, every three days, or every week. The FT page breaks the data down by country, a number of regions, as well as major cities. There's a lot of information on that page, it's well worth a visit (and freely accessible right now, too).

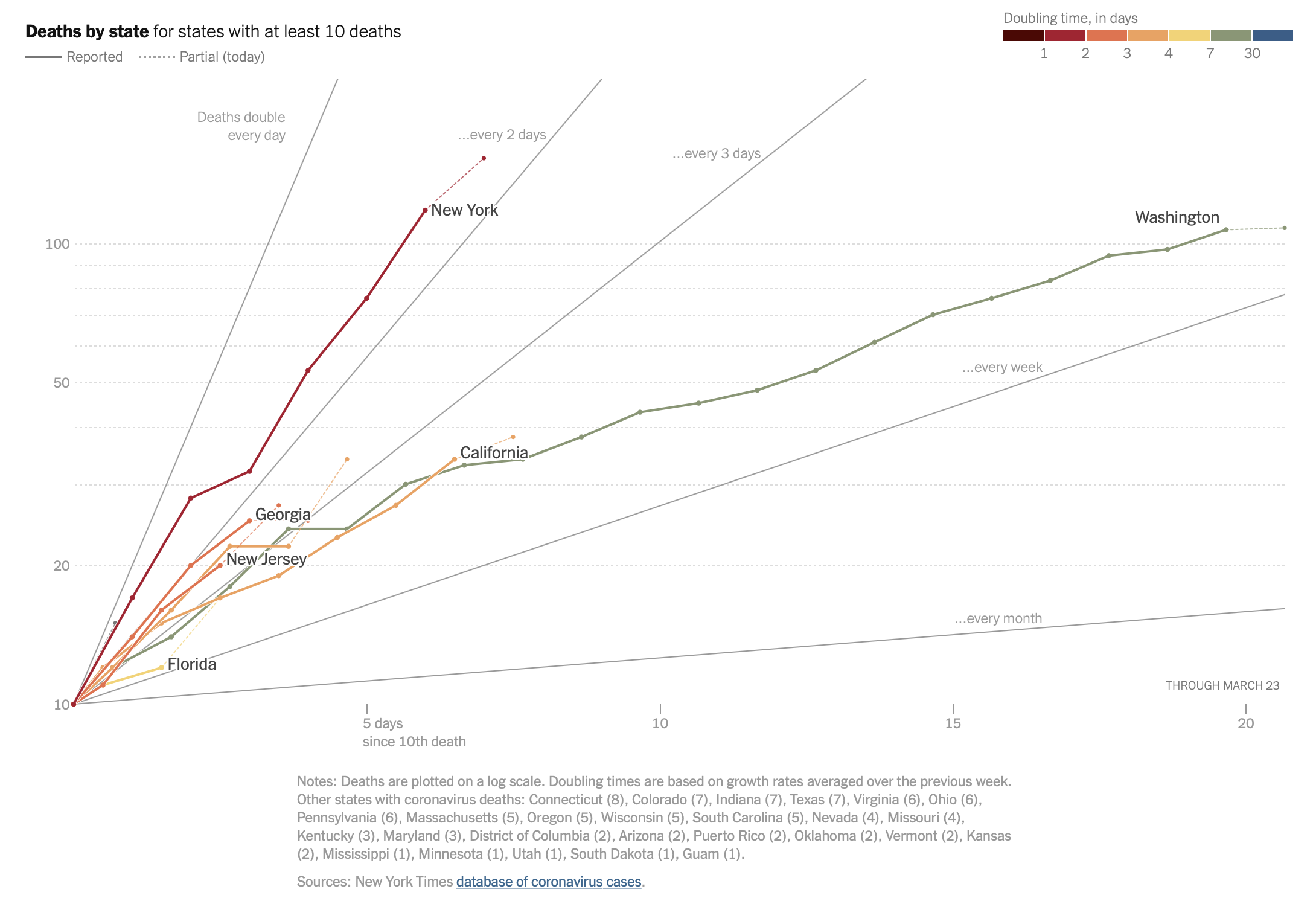

John credits Lisa Charlotte Rost and her post on the DataWrapper blog with the idea. Josh Katz and Margot Sanger-Katz at the NY Times are using the same technique on their coronavirus tracker as well, breaking the data down by country and a number of U.S. states. As I'm writing this, the outlook for New York is not looking good.

It's amazing what a simple graphical element can do for context in a visualization. It turns a mere display of data into an informative piece of journalism.

Posted by Robert Kosara on March 23, 2020. Filed under Visual Communication, COVID-19.