Dealing with Paper Rejections

For some reason, the topic of reviewing and getting papers rejected came up several times in conversations at VIS recently. Getting your work rejected and learning to deal with rejection is part of life as an academic, and it’s worthwhile to think about the process a bit.

I’m basing this on a nice piece by Niklas Elmqvist titled Dealing with Rejection, so read that first. His perspective is that of the nice academic (and recent InfoVis papers chair). My perspective is less academic, and a little less nice.

The First Response

Here’s what I do when I get a accept/reject notice. First, I scan it to figure out if it’s an accept or reject. Unfortunately, many conferences and journals make this much more annoying than necessary, burying the salient piece of information in lots of boilerplate bullshit. You can usually tell from expressions such as “we regret to inform you” or “unfortunately” that it’s not good news.

So it’s a reject. What now? I usually do this:

- breathe

- read the summary review

- stop

At this point, I know I’m not very rational, so I don’t read any of the individual reviews. There’s no point. All my brain wants to do is argue. After a day or two of letting it sink in, I can read the remaining reviews and think about what they tell me.

The initial blind rage is also the wrong time to decide on a response. Don’t email the chairs. Don’t post reviews (never do that, see below). Don’t decide to quit research and become a hermit in a cave.

After a day or two, you’ll be in a much better place to rationally think about what to do. That's when you read the detailed reviews. That’s also when you can decide to take unusual steps, if you really still feel the need.

The Worst Reviews from the Worst Reviewers

The review process is not perfect. Some reviewers don’t read your paper carefully. Some don’t like one little detail and then start picking your work apart because of that. Some take out their personal problems (or their own last rejection) on your paper. We’re all human, this is not a perfect system.

Sometimes, the reviews are just downright stupid or off-topic. When we submitted the connected scatterplot paper to InfoVis last year, we got fairly good reviews overall. The paper was killed by the primary reviewer, who had some other paper in mind and didn’t seem inclined to accept the existing paper because it didn’t match his idea. We resubmitted the paper with only very minor changes to TVCG and got it accepted with no problem.

Getting the right reviewers is unfortunately a lottery. Sometimes you win, sometimes you lose. The problem is that there is no way for authors to provide feedback on review quality. InfoVis and a few other conferences have started a little bit of tracking where primary reviewers can rate review quality, but that doesn’t help you when the primary is the problem. I also don’t know how many people ever bother with these ratings, or if they have any sort of consequences.

Complaining to the Chairs

Don’t. It won’t help and you’ll just look like a crybaby. Unless there is an egregious problem, the chairs are not going to change their mind. They’ve spent a ton of time reading reviews and making decisions, they’re not going to change those. And with a conference, they usually can’t, since they have a limited number of papers they can accept.

The same is true in the rebuttal: if I’m a reviewer and your rebuttal is angry or whiny, or if you accuse the reviewers of being stupid or not having read your paper, I’m not going to change my mind. You should point out things that the reviewers might have missed, but do it in a respectful way. And if all of them missed something, perhaps you need to do a better job explaining it or pointing it out.

Posting Reviews

One particularly problematic thing Niklas mentions is posting reviews online and commenting/venting. Don’t. This is even worse than complaining to the chairs: now not only they will take you for a crybaby, but anybody who sees this will, too. Don’t think that just because you think those reviews are completely unacceptable, others will too. Especially without the context of having seen the paper, the reviews will look very different to others. This is not something you can win.

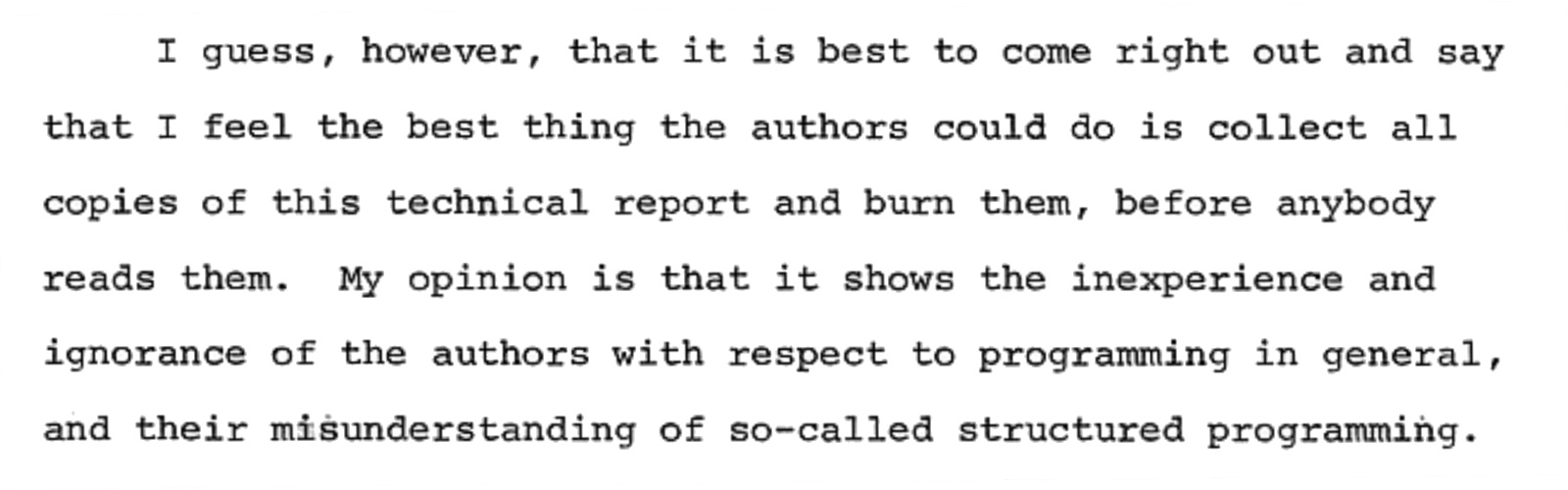

There is one exception. While Niklas clearly says to never post reviews, he also links to this rejection letter that Ben Shneiderman has posted about the structured flow-charts/Nassi-Shneiderman diagrams paper.

It’s important to note a few things here, though. This is a particularly dumb and nasty letter, yes. But it was also posted by Ben Shneiderman (i.e., somebody of significant standing in the community, not just a random grad student or young professor), and he did it 30 years after it happened.

So if you’re the next Ben Shneiderman, and you keep your rejection letters around forever, this is a potential thing to consider. In fact, it would be quite fun to see reviews (positive and negative) for seminal papers after 20 or 30 years have passed.

I also like Ben’s open discussion of how people were trying to rip him off back then. This is not something we talk about a lot, and it usually doesn’t happen after publication. It’s also generally very rare in visualization, from what I can tell. But I’ve seen some contentious situations where people were working on similar ideas and fought hard (and not always in the nicest of ways) to get their work out before the others.

Reviewing in Visualization and HCI

All of the above focuses on the negative. Yes, there are poor reviews. Yes, there are careless and sometimes mean reviewers. But in general, reviews in visualization are pretty good. They tend to be a bit on the critical side, but they’re usually fair and reasonable. And we don’t have the problems many other fields have, where there are different schools of thought that are at war with each other, or where big names get you into a journal or conference even if the work is sub-par.

Is it perfect? No. But it’s pretty good. And while any individual rejection sucks, it still happens in the context of a system that largely works.

So when you get your next rejection: read the summary, breathe, and then give it some time. It’s not the end of the world.

Posted by Robert Kosara on November 13, 2016. Filed under peer-review.