What Happened to ISOTYPE?

Jan Willem Tulp asked me an interesting question on Twitter last week: if ISOTYPE was so great, why isn’t anybody using it anymore? Here are some of my thoughts, but more than that I want to see if anybody has more idea, and maybe even a bit of evidence, on why ISOTYPE fell out of fashion in the 1950s and hasn’t really come back since.

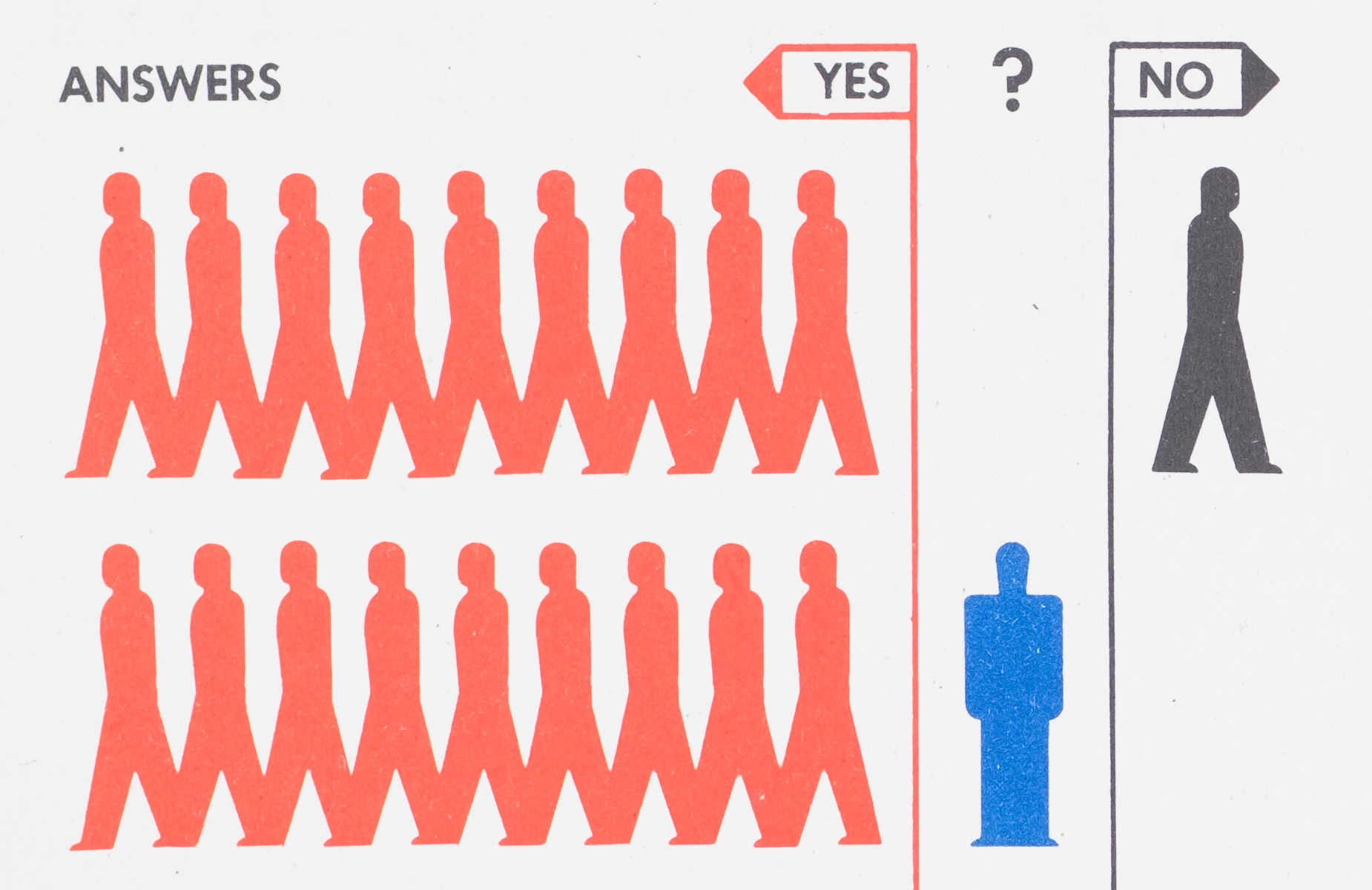

The Heyday of ISOTYPE

To set some context, ISOTYPE wasn’t just a neat idea. I’m aware of at least 70 books that use ISOTYPE charts from the 1930s through the 1950s, and I actually own copies of close to 50 of them. Yes, you read that right. I’ve posted a handful in this series, and I intend to scan and post a lot more of them in the near future.

The ISOTYPE institute was around for several decades and produced a graphics for dozens of books and other media using their technique. A few others picked it up and produced more, most notably Rudolf Modley who designed around 1,000 Telefacts that ran from 1938 to the mid 1940s in American newspapers.

What Happened?

I really want to pose this as a question, but here are my thoughts. I hope others can chime in with more ideas, and hopefully some evidence, because all I have here is speculation. But speculation held with conviction.

First, Modernism happened. This one’s a bit complicated because it’s clear that Gerd Arntz’s designs of the iconic shapes used in ISOTYPE have become, well, icons of modernism. At the same time though, the idea of using such shapes in data displays may have been a victim of modernist ideals that eschew all decoration. These ideas go back much further than the 1940s of course, but became much more widespread mid-century.

Another reason might be the tighter coupling of statistics and charts, specifically John Tukey’s Exploratory Data Analysis. The charts used in the process of data exploration and analysis had to be made relatively quickly, so there was no time to consider the right kinds of shapes to use. ISOTYPE also isn’t exactly the most information-dense format, and it’s largely confined to the equivalent of bar charts, no continuous variables or two-axis plots like scatterplots are possible.

Also, Tufte happened. Tufte has had a huge influence on what is considered good and proper data visualization, and he has no patience for decoration or the ‘pop journalism’ of ISOTYPE (he also considers the charts ghastly). Anything added to the pure data is considered chart junk in the Tuftean world, and so we end up with a style of data representation that has had all of the fun and explanatory power of images and text beaten out of it.

And then, computers happened. This is somewhat connected to the point about statistics above. The way we deal with data is not to spend a lot of time on individual data sets or questions, we want general and efficient ways to turn any amount of data into visualizations in an instant. Computers are good at that, but much less so at thinking up clever icons to go with the data. Early computers and software (especially in 60s, but well into the 80s) also couldn’t to much beyond drawing points, lines, and rectangles, so the charts that consisted of them were the ones that got made: scatterplots, line charts, bar charts.

While it’s easy today to draw any shape we want, visualization tools and libraries are still very limited in one important way: they almost universally assume that each item in a table or result set (when talking to a database) corresponds to exactly one mark. ISOTYPE needs multiple marks per value though, which requires workarounds and hacks in virtually any tool and toolset/library you will find today.

Surely, academic research is not limited by the tools though, right? My colleague Michael Correll nicely summarizes the possible reasons for the lack of academic research interest in his usual bleak and succinct way.

perhaps because isotypes are easy to understand and can be both constructed and interpreted reliably even by children, and both tufte-ism and academic vis require that vis be either a "technology" or "science" depending on the rhetorical project at the time

What Do You Think?

As I said, I’m really looking to learn more about the why here. What do you think? If you have further ideas, and in particular evidence, please let me know!

Posted by Robert Kosara on September 28, 2020. Filed under isotype.