Beyond the Knee-Jerk Reaction

There is a tendency to just reflexively make fun of certain types of charts, in particular pie charts and 3D charts. While that is often justified, there are also exceptions. Not all pie charts are bad, and not all 3D charts are terrible. But to spot those outliers, we have to suppress the knee-jerk reflex and give them a moment of thought before ripping them apart.

The Chart

About two weeks ago, I posted this chart on Twitter after seeing it in the Wired iPad app (September 2014 issue).

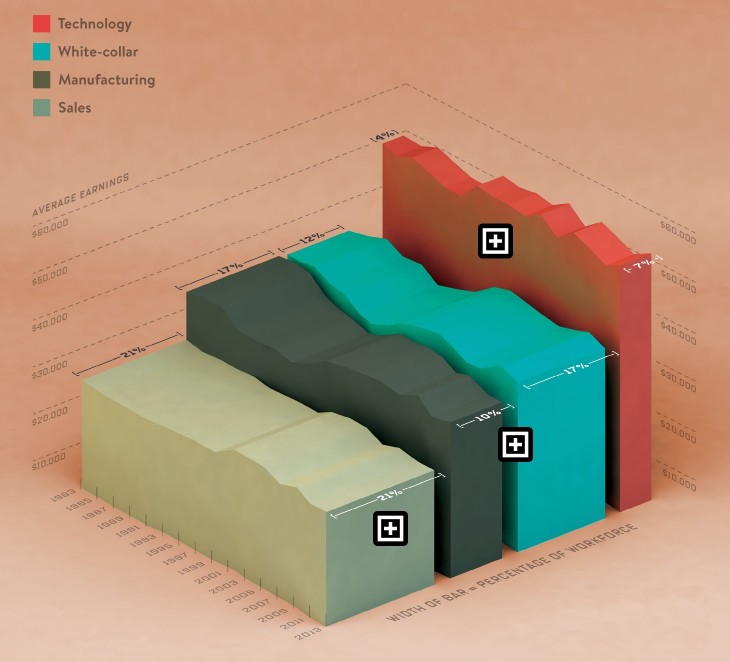

Yes, it is a 3D area chart. The vertical axis is the average salary paid in a number of sectors over time. The one horizontal axis on the left is the time axis, showing 30 years from 1983 to 2013. The other horizontal axis divides the chart up into four elements for four sectors: technology, white-collar, manufacturing, and sales. That axis has a second encoding in the width of the “mountains,” which represent the fraction of the workforce in each of those sectors.

The Good

So there’s a lot of data here. You can see that the tech sector pays a lot more than the others, roughly twice what sales pays, and a good 50% more than manufacturing or white-collar jobs. You can also see the effect of the recession in the ripples along the tops of the mountains, with an interesting lag between white-collar/manufacturing and sales.

I also have to admit to being quite surprised to see how small the tech sector really is: only 7% of the workforce, up from 4% 30 years ago. It’s sometimes hard to remember that there’s a world beyond technology when you’re working at a software company and spend your days on Twitter. White-collar jobs have grown to roughly make up for the loss in manufacturing, but not quite, while the percentage of people in sales has not changed.

Not all of that comes from the chart, it certainly requires some reading of the numbers, in particular for the width of the mountains. But the information is there and it’s not hard to read. The reason for posting this was my surprise at finding myself spending several minutes with this chart and finding it quite informative and fun to explore. There is a bit of interaction too, when you tap on the plus signs, but those don’t give you much additional information.

The Bad

What is wrong with this chart? Sure, it’s 3D. You can’t precisely read the numbers. What was the average salary for manufacturing jobs in 1992? You can’t read that with any sort of precision. 3D is wasteful, you could show more data in that space. But who cares? That is not the point of this chart. You can see the development over time, that’s what matters. And the chart does not seem to wildly distort the reading of those values that are readable (which is a common issue with 3D charts).

I also think that this is a good way to present what are basically eight time series (salaries and workforce percentages for four sectors) in a very concise way that works well in a static image. Of course this could be broken up into two or even three charts, but you would lose some of the cohesion the 3D gives you here. And it would be a lot less fun to explore. The lines for workforce percentage would also look extremely boring (they seem to be changing at a fairly constant pace, and certainly don’t change direction). If you care not just about representing the data but also capturing readers' interest, this is the better chart. It certainly worked in my case.

A Smarter Discussion

But beyond all those reasons, I just want to see a more nuanced and informed discussion of these things. It doesn’t take much intelligence to sneer at every 3D chart and every pie chart that floats by on Twitter. But things are a bit more complicated than that, and these things do have their place. And just throwing some supposed absolute rules around doesn’t do anybody any favors.

Perhaps Christopher Ingraham was right.

https://twitter.com/_cingraham/status/508336378279886848

But I hope that we can get to a point where we can have a more intelligent, nuanced, and respectful discussion. We’re not going to make much progress if we just keep rehashing the same old ideas without putting any new thoughts into them.

Posted by Robert Kosara on September 15, 2014.