A Maze of Twisty Little Passages, All Alike

Theoretical research is a tough sell, and not just in computer science. Not only are we expected to produce things we can demo, it's also hard to tell beforehand what exactly the results will be. But that is exactly why we need to do research: because we don't know. Applied research is obviously important, but the current trend towards only applied work is worrying.

Mark Changizi put it well in his piece P, NP, And Is Academia Inhospitable to Big Discoveries?

The problem is simply this: You can't write a grant proposal whose aim is to make a theoretical breakthrough.

"Dear National Science Foundation: I plan on scrawling hundreds of pages of notes, mostly hitting dead ends, until, in Year 4, I hit pay-dirt."

Theoretical breakthroughs can't be mapped out in advance. You can't know you've broken through until you're…through.

…at which point there is nothing left to propose to do in a grant application.

This is a problem I've run into myself a few times. When writing a proposal, I'm supposed to know what I'm going to do and how I'm going to do it. That may be the case for the first few steps, but if I already know what I'll do after those, what exactly is the point of doing the research?

And it's not like funding agencies like the National Science Foundation (NSF) weren't interested in foundations. I've spoken to program officers who have told me that they're tired of all the tiny variations on techniques and want to see more fundamentally new stuff. Alas, that kind of work does not seem to make it through the review panels.

Much of the work I've done over the last few years could not have been foreseen. Caroline Ziemkiewicz and I were looking into why different papers that studied tree visualization techniques came to different results. Little did we know that this would lead us to further work on design criteria in completely different visualization techniques, a study of perceived movement and dynamics in static, abstract images, and work on which visual properties provide the strongest connections in a network graph.

When you're working on a particular practical problem, you might not know what will work best, but you usually have a pretty clear idea what you'll want to try. And even if you don't end up with a completely new design, you will get some kind of result. That is not the case when you're exploring unchartered territory in perception or modeling. You might not end up with anything. And even if you do, your path there will not be a straight one.

To add insult to injury, the results often seem obvious and easy. Few people realize how much experience, design, effort, blood, sweat, and tears it took to produce a seemingly simple but fundamental result. Some of the more recent proofs, like for the Poincare conjecture or the P!=NP problem, are very long, complicated, and impossible to follow for all but a few specialists. That suggests that they required a lot of work, but what about the elegant, simple things? Boiling something down to a few seemingly obvious steps takes a lot of effort, and it seems to often have the effect of making the achievement seem smaller.

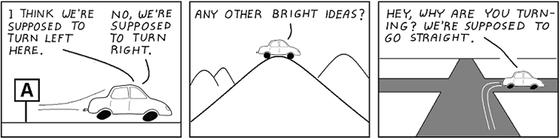

As a final illustration of the point, here's a comic from abstruse goose that I think is incredibly accurate (click for a slightly larger version). Give it a bit of time, trust me. Like all fundamental things, it takes a bit to sink in.

Posted by Robert Kosara on August 12, 2010.